The age of Atlanta, mapped, and buildings worth visiting

By Maggie Lee

(Longform version of story from SaportaReport, Dec. 31, 2017)

On New Year's Day in 1848, the perhaps 2,000 people of the little settlement of Atlanta celebrated as a official city for the first time. Just three days before, the governor's signature on a charter created a tiny city centered Downtown.

Fairly few buildings those first Atlantans may have known still survive.

The city hit a growth spurt as the 19th century became the 20th, and streetcars and automobiles arrived. More folks began to build homes and shops in areas like Edgewood, Kirkwood and West End. With cars, people built yet further out, to places like Home Park, Virginia Highland, Candler Park, Sylvan Hills and Washington Park.

We can get a visual idea of when and where Atlantans have built and rebuilt, by checking out this map, which matches a construction year to about 118,000 homes, offices, shops and other buildings.

Take the data with a little grain of salt, however. It comes from records created, and sometimes lost or damaged over more than 100 years. It comes from deeds, tax records, maps, even aerial photography, gathered by humans and computers in two counties for generations. Especially where buildings are very old or close together, there are some shortcomings. Read the data FAQ here.

We also asked some Atlanta architects, historians and preservationists to pick out some of the buildings they think are most worth seeing, for beauty, for history, for any reason. Those follow the map.

In some parts of Atlanta, newer construction has replaced homes which were built as the city expanded from Downtown.

(On a small screen? Use the fullscreen  button on the map for a bigger view.)

button on the map for a bigger view.)

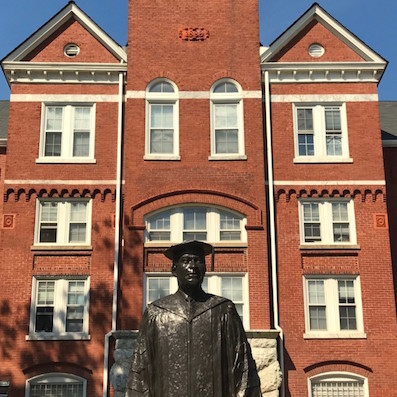

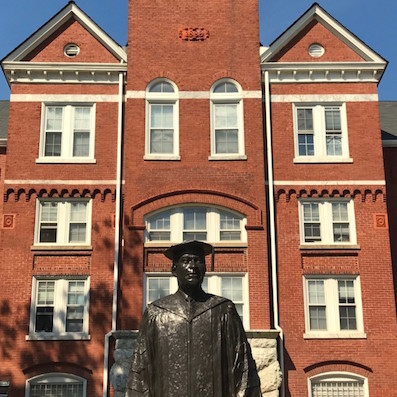

Examples of early Atlanta University, Morehouse and Spelman buildings

Vine City and AUC

Gaines Hall (1869, AU) and Fountain Hall (1882, AU)

North and south sides of 643 Martin Luther King Jr. Dr. SW

Knowles Hall (1884, AU)

Beckwith St. SW

Graves Hall (1889, Morehouse)

Near the corner of Lowery Boulevard and Atlanta Student Movement Boulevard

Spelman's Rockefeller, Packard, Giles, Morehouse-James, MacVicar halls and Reynolds Cottage (1886 - 1901)

Along The Oval, near Spelman Lane

Dating as far back as 1869, some of Atlanta's oldest buildings also sit in an unusually large collection, on the adjacent campuses of Atlanta (now Clark Atlanta) University, and Morehouse and Spelman colleges.

"I think the architecture is outstanding for this period of time," said architect Arthur Clement of Silverman Construction. He's worked across the state on college builds and renovations and is now working on a book about the architecture and campus development of Georgia's historically black colleges and universities.

Architecture, like fashion, goes in phases, he said.

The fashion then for folks building multipurpose educational buildings, was red brick with a range of influences: Italianate, Queen Anne, Romanesque Revival.

John D. "Rockefeller used his personal architect ... to design some of the [Spelman] buildings, Morehouse-James Hall, Reynolds Cottage which is where the president resides; you've got the first African-American hospital, MacVicar," said Clement.

"When you look at the plight of African-Americans in Atlanta, you can't not look at these places, campuses, that tended to be the largest areas that were built for them, that they had control and use of in a segregated society," he said.

Nedra Deadwyler also named Gaines and Fountain halls as places to see. She's founder of Civil Bikes, a tour company that focuses on history, art, culture and Civil Rights sites. What she brings up is the importance of the studies that went on in those buildings, naming in particular sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois.

His years in Atlanta around the turn to the 20th century as an AU professor were productive but painful. He documented things like the accumulation of land by African-Americans after emancipation and the Georgia prison-industrial system's exploitation of black males. "We had someone of his caliber, who was underrated as a sociologist, his work was studying black people, black Americans, his work never received the credit in mainstream American academia," said Deadwyler.

But Gaines Hall has been damaged for years. It's roofless after a 2015 fire and is part of a custody battle between the city, which has claimed it purchased it and surrounding property from a struggling Morris Brown College, and Clark Atlanta University, which has challenged the sale and claims ownership.

The West End home known as The Wren's Nest started life in 1870 as a farm house constructed by George Muse, founder of Muse's Clothing. But the Queen Anne style Victorian home seen today dates from extensive 1884 renovations during the time it was owned by Joel Chandler Harris, writer of the Uncle Remus folk tales.

It's a beautiful building that evolved from something much simpler, said Derek Anderson, a historian by day, who with his wife and a friend run the Architectural Splendor Instagram account.

"It's located in ... one of my favorite parts of town. West End in general I would say is a neighborhood that has some really incredible architecture," he said.

A horse-drawn trolley line reached West End from Downtown by 1871, helping make it a popular white middle- and upper-class residential suburb around the turn of the 20th century for the likes of former governors and well-to-do folks. Many fine old homes are still standing and are open sometimes on a tour of homes. Check West End Neighborhood Development to read more about the neighborhood, or just have a walk around.

The Wren's Nest itself is open as a museum.

Cabbagetown homes and mill

Cabbagetown

East of Oakland Cemetery

The area just east of Oakland Cemetery began its life as a mill village in the 1880s and 1890s. The buildings of the Fulton Bag and Cotton Mills complex were put up between 1895 and 1922, according to the city's application to put Cabbagetown on the National Register of Historic Places. The homes broadly get newer from the west (about 1885) to the east (the 1920s.)

"You can kind of see the progression of the different houses of different sizes and different styles in the neighborhood, depending on when they were built, but then also ... depending on whether you were a mill foreman or a maybe a worker just a little lower on the totem pole," said Derek Anderson, the historian.

There were already folks living in the area before the mill opened, but the mill did come to build or own many of the residences there. The home types include tiny shotgun houses, gabled "ell" cottages in a T- or L-shape and multi-family duplexes of a type typical in mill villages.

One legend has it that the name "Cabbagetown" came from the smell of supper one night after a cabbage truck overturned in the neighborhood and people got the produce, one way or another. Another version has it that poor mill folks regularly cooked cabbage, lending their village a name. Another says that people there just grew cabbages. The truth may be unknowable.

In 1904, Rhodes Hall joined the mansions of Peachtree Street as the home of furniture magnate A.G. Rhodes and his family. From electric light bulbs to stained glass to the huge estate on which it sat, it exuded opulence, arguably the finest jewel on a long string of sparkling residences along Peachtree in the old days. Very few Georgia residences were ever built in such a style.

It also happens to be in the hands of an excellent steward, The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation, a nonprofit. Their office is there, but is also available for event rental.

Consider yourself invited in by Trust President and CEO Mark McDonald. "If you haven't been there, you need to see it because we just finished an interior restoration and new landscape," he said. It's open Saturdays, but you can tour at other times by appointment. Check the website for details.

Dating from 1905, folks working in the little Interlocking Tower, or "switch tower," set the signals that controlled train traffic around Atlanta's vast Terminal Station. It's thought that the two buildings share the same architect, P. Thornton Marye, who also designed the Fox Theatre.

"The switch tower down there in the Gulch is a little yellow brick building, it has a clay tile roof, it's like this little vestige" of the Terminal Station, said Scott Morris, a historian who works for New South Associates.

For much of the 20th century, Terminal Station is the first thing people saw when they arrived in Atlanta via train, the same way airport is the gateway to the city today. Atlanta's Hotel Row was within walking distance on Mitchell Street. In 1933, what's now the Martin Luther King Jr. Federal Building opened as a post office, the location chosen because it was close to the rail terminal. Terminal Station closed in 1970 and was later demolished.

Morris said the little tower makes him think when he walks by.

"I think about how it relates to a grand building and to Atlanta's history and the early architecture and the intersection between transportation and architecture," he said.

Complete by 1910, the Herndon Home would never house the woman who designed it, Adrienne Herndon. One-half of an Atlanta power couple, she died just before construction was done on the opulent home she was to share with her husband, Alonzo Herndon.

He was a man born into slavery who made himself into a magnate, first in the barbering business, later in insurance. She was an actress and a professor at Atlanta University.

The home has a great neoclassical revival style, said Derek Anderson, the historian. And it's notable for having been designed by Adrienne. "Women didn't often get the credit back then for that sort of thing," he said.

The grand home is now open as a museum that showcases the taste of the Herndons and their time.

Planning a visit? It's on the same block as Gaines Hall and Fountain Hall is one block south.

Finished in 1912 and 1913 respectively, the Odd Fellows Building and Auditorium rose at a time when Jim Crow was at full strength in the South, legalizing the distant second-class status of black Americans relative to whites. The buildings and their histories evidence some African-American coping strategies in a hostile world: self-help, entrepreneurship, accumulating wealth, spending wealth at black-owned businesses and even elevating skilled labor to a literal work of art.

"Through Jim Crow, it was a space for blacks to go to the theater, they didn't have to sit in a segregated place," said Nedra Deadwyler of Civil Bikes. "There were businesses; entrepreneurs could have storefronts, offices, from banks to the pharmacy, an optometrist, a haberdashery. It was a center of entrepreneurship, a commercial and social space."

The Odd Fellows, one of several fraternal organizations with Auburn Avenue offices, raised the money for the buildings and used the proceeds for the Odd Fellows Endowment Fund. That fund paid benefits to seriously ill members and death benefits to their widows, according to the city's application to the National Register of Historic Places. Spearheading the work on the Odd Fellows Building was one of its leaders, Benjamin Jefferson Davis Sr., editor of the Atlanta Independent newspaper. (Check out scans of the paper from September and October 1913 for its auditorium opening coverage.)

Deadwyler pointed out that sculptures outside Odd Fellows show people who have recognizably African features.

"Their hands are at work ... they're holding mallets and hammers. It really goes to speak to the ethos of the builders, the Order of the Odd Fellows," she said.

Completed in 1914, the Healey Building carries the name of a family of early Atlanta developers. William Healey ran the company when it was built.

It was a skyscraper by the standards of the day. And had World War I not started, it might have been two skyscrapers: original plans called for twin towers.

Mark McDonald, from the Georgia Trust, said it's one of his favorites.

"It's got a Gothic Revival interior in the atrium. It's quite a 'big city' building and it really shows how prominent Atlanta was in the late 19th and early 20th century, the sophistication architects brought to the city," he said.

It's a private building today, but there is a coffee shop on the ground floor that has some seats looking into the lobby.

The Capitol View Masonic Lodge was completed in 1922, with space for retail on the first floor, and an auditorium, offices and ritual space on upper floors, according to a neighborhood application to join the National Register of Historic Places. (Available as a very large PDF.)

Scott Morris, the historian, said that he thinks it is the kind of thing that gives "mixed-use building" a good name, not the image often conjured up of an overwhelming huge new development.

"It's this truly mixed-use building that was designed to serve a neighborhood. I think it's a great-looking building and just kind of a cool reflection of that first half of the 20th century, a big, neighborhood kind of mixed-use building," he said.

What opened in 2014 as Ponce City Market debuted as a Sears, Roebuck and Co. store and warehouse in 1926. In between, parts of it housed a branch of city hall, a trade show space, a gym and other tenants.

Today, light shines through its massive windows into residences, shops and a food hall adorned with old machinery, a nod to the masses of merchandise that used to move through its levels.

The overhaul is a "game-changer," said architect Bill Clark, incoming president of the Atlanta chapter of the American Institute of Architects. Though, he admits to a little bias: he's also Atlanta office president of Stevens & Wilkinson, a firm that worked on residential parts of the PCM redo.

"To me, it's just changed the whole architectural approach to older architecture in our city," said Clark.

"It put us on the radar I think, to show that we can be in that realm of architecture and be stewards of older architecture and do it well and be attractive. I think a lot of the buildings the older structures, along the BeltLine for instance, are taking cues from that," he said.

The Southern Bell Telephone Company Building isn't quite what it might have been. Opened in 1929 and still impressive, it's actually only about half as tall as originally envisioned.

"It was pre-Depression ... Southern Bell wanted to express that telecommunications were this powerful thing, and they were going to represent that power with this big Art Deco building," said Scott Morris, the historian.

It's a little more tame than say, New York City Art Deco, he said, but it's still got those streamlined qualities, geometric relief sculptures, lighting, all in that style.

That kind of early modern style, seen on buildings like the MLK federal building and the 1930 part of City Hall, are stylistically representative of the idea of Atlanta as this city of progress at the time, he said.

It is the only good example in Atlanta of the "modernistic style," according to a statement prepared by the city to nominate the building to the National Register of Historic Places. The same article points out that it's very different from more of a throwback-inspired building that opened about the same time: the Fox Theatre.

Today, signs out front carry the name of the successor company: AT&T.

Philip Trammell Shutze, born in 1890, was already renowned in his lifetime for his elegant work. In Atlanta alone, his existing buildings include the Swan House at the Atlanta History Center and the Goodrum House at 320 West Paces Ferry Road.

His H.M. Patterson & Son Spring Hill Chapel opened in 1928. The Midtown mortuary is endangered now because it's on such a large piece of property, said Mark McDonald, from the Georgia Trust.

"I would say people need to see that one because it may not be with us much longer," he said.

Shutze also designed The Temple, which opened in 1931 as a new home for Atlanta's oldest Jewish congregation, a force in pushing for a more educated and fair city.

In the 19th century, years before the current Temple was built, the first rabbi of the congregation founded a school which is seen as a forerunner of Atlanta Public Schools. Over the years congregation members organized to fight for the likes of an eight-hour work day and the end of child labor.

The Temple itself was bombed in 1958, because of some combination of anti-Semitism and Rabbi Jacob Rothschild's vocal support for black civil rights, racial integration and his friendship with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

History is one, but only one, reason why Bill Clark, the architect, named it among buildings to see.

"Not only was it designed by Philip Shutze, but it's timeless. And there's just so much incredible history there," said Clark, who has worked on renovations to the classical-inspired red brick edifice.

"I think some cities can be judged in some respects by their public architecture, their religious architecture and their museums. And this is just a wonderful example of architecture in the religious realm," he said.

One of the first places in Georgia to see the influence of a key modern design school from Europe was another school: Georgia Tech.

P.M. Heffernan taught at Georgia Tech starting in 1938, and he was made director of the school of architecture in 1956.

Heffernan's time as director of the school of architecture saw a shift from Beaux Arts, classical style education to a more modern approach influenced by the Bauhaus, said architect Nathan Koskovich, principal of Koskovich Architecture and board chair of Atlanta's Architecture and Design Center, a nonprofit that aims to promote high quality design and connect Atlanta's design culture to the world.

Due to the purchasing rules of the time, Heffernan and other professors at Georgia Tech were able to design buildings on campus. "This lead to Georgia Tech having many of Georgia's earliest examples of Modern Architecture," he said.

It's easy to speed by the long, low Rollins office building on Piedmont Road by the MARTA rail yard. But if you don't slow down or you're not on foot, you'll miss a fantastic example of the midcentury modern aesthetic, according to Scott Morris, the historian.

The Orkin pest control corporation moved into their newly constructed headquarters in 1963. The sign out front now says "Rollins" as well, for the company that took over Orkin. The building still looks like the future that The Jetsons promised us.

Though we don't have flying cars, the building does communicate with the street and pedestrians via stairs to the sidewalk. Morris admits to having peeked in the windows and reports period touches like wood paneling and red carpet.

"It's this cool, interesting, modern for the period, Modernist architecture, corporate campus that really is representative of that era, of the 1960s, of commercial and economic development for the company and for the time period," he said.

Going to visit? Pair it with Henri Jova's nearby 'round bank' at 2160 Monroe Dr. NE.

The Hyatt Regency opened Downtown in 1967. A few years later, a high school boy from Tennessee visited.

"It just totally blew me away, coming from a small town, I had never seen anything like that before," said Bill Clark. It cemented his plan to become an architect.

It was an early building from one of the world's best-known architect-developers: John Portman. Born in South Carolina, his distinctive buildings tower blocks and blocks of the city where he grew up and made his career: Peachtree Center, AmericasMart, Westin Peachtree Plaza and the Marriott Marquis.

Portman's Hyatt took a modern approach to the age-old concept of an atrium: an open space inside a building. But in the Hyatt's case, it's a stunning open space 22 stories high, ringed by halls, pierced by elevators and covered with a skylight.

"At the time it was cutting-edge, and pretty risky," said Clark. "What an important building in our city too."

Portman's own designs now soar into skylines all over Asia, and his work has influenced architects worldwide.

Since the day in 1979 when it opened, there's been a skyline view from King Memorial MARTA station, between the elevator and the ticket machines. Depending on the light, the time of year, the time of day, the feel in the station itself is different.

"I kind of look at King Memorial MARTA station as this sculpture in the sky, these crazy concrete forms, there are these staircases and elevators cascading off of it," said Scott Morris, the historian. From the platform upstairs, the openings alternately reveal and hide the light and the views toward Cabbagetown, Sweet Auburn and Downtown.

Morris said he credits the development of MARTA itself with helping to spark interest in public art, like the sculpture "Aspirations" at the station.

But that clear skyline view? It's on par with the one from the Jackson Street bridge, the one at the start of the TV show "Atlanta," said Morris. But it's also outside the gate: you don't have to pay $2.50 to see it.

Opened in 1980, the Central Library and headquarters of the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System has its fans and those who aren't so much.

It looks like a jail, said Robb Pitts in 2016, who was then out office but is about to be sworn in as the Fulton County Commission chair. That was amid talk of downsizing or closing the library and replacing it with a new structure.

But the folks of the Architecture and Design Center are among its fans. They started a petition urging the library board to protect it from any demolition or damaging renovation.

It's by architect Marcel Breuer. The Central Library wasn't only his last work, but his greatest, said Nathan Koskovich, the architect who chairs ADC.

The Hungarian-born Breuer, later in his career, experimented with forms that had the monumentality of classical architecture but were distinctly modern, Koskovich said. He said it features a Breuer signature idea called "heavy lightness," characterized by concrete forms that increase in size as they go up over an apparently fragile glass base. Yet it's got a human-scaled entry portico. He said he thinks the exterior panels on the library are more interesting than at the perhaps more famous Met Breuer Museum in New York. On the library here, the cross-hatching reveals warm colored stone aggregate, and placement of panels work with the weather to create a shadowlike pattern on the panels. The courtyard on top is one of the nicest spaces in Atlanta, he thinks.

"While the monumental style of the building is foreign to a lot of people, I think the lack of proper maintenance, and some unfortunate renovations have really muted the qualities of the building," he said.

Today's Sweet Auburn is vibrant, many of its landmarks are preserved, and there are monuments to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in several parts of the city. But it wasn't always like that. The road to all that goes right through a 1981 building.

What's now the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change started in 1968, when an assassin made Coretta Scott King a widow and she began efforts to memorialize her husband and his work.

And the headquarters would be in Sweet Auburn. The 1970 crypt was just the first step.

"To Coretta Scott King's credit, she used the King Center as a way to revitalize that neighborhood," said Arthur Clement, the architect.

He said the ensemble of buildings is important in one way for the design by J. Max Bond. The Center houses archives, an auditorium, exhibits and offices under its barrel-shaped roofs and within its brick walls, which wrap around the outdoor fountain and crypt. But the Center is also important for all its preservation and memorial efforts.

When Coretta King got started, there was no national historic site, King's birth home wasn't open to visitors and there was no King holiday.

"Coretta Scott King had an uphill battle to build the Center, to get the holiday established. We come along now and accept that as a fait accompli but it was not," said Clement.

Architect Richard Meier's High Museum opened in 1983; in 2005, an addition by architect Renzo Piano opened.

They move the city further along a journey, in Bill Clark's judgment.

"It goes back to, you judge cities on their public architecture, their nonprofits, and their art and culture," he said. Atlanta is somewhere in the middle of a journey, he said, and doesn't compare to places like New York and Chicago. But the formation of a museum and the construction of such a home for it is important.

"We had two of the basically the worlds most significant architects ... just creating a culturally rich, wonderful building. It continues just to get better and better," he said.

Clement adds the adjacent Woodruff Arts Center and the outdoor space created among the buildings into his reasons for visiting the complex.

"You go up there and it's an active area, they have artwork, I think that's a very successful example of buildings working together to enhance the life of the city, where people can come and congregate, do different things," he said.

It's true, the Krog Street tunnel isn't a building, but it is a landmark because of the way people make the concrete canvas their own.

Folks have been probably been tagging the tunnel for decades. But a look through the AJC stacks suggests a turn from hasty vandalism to painters of a more expressive frame of mind came in the last years of the 20th century. The tunnel itself dates from 1913, according to a carving along the Wylie Street side.

The art and messages in the tunnel change every time someone shows up with a paintbrush or a new stencil: a shrimp with the head of Donald Trump, a grinning gold-toothed rat, blue Frankenstein with headphones, an announcement about a holiday market. And if you're not driving, you're probably taking pictures.

Marc Johnson admits the first time he saw the Krog Street tunnel, he, well, thought it was an "eyesore." But now, the architect at Fitzgerald Collaborative Group said he's grown to appreciate it.

"It just strikes me, I love the energy," Johnson said.

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights opened in 2014, houses exhibits not about the distant, unknown past, but about things that are well within living memory: mugshots of Freedom Riders, a lunch counter sit-in simulation.

Many visitors probably feel a personal connection. Architect Marc Johnson does.

For him, the Center came with a feeling of personal responsibility too. He worked on it, tackling problems like how to make sure papers of Martin Luther King Jr. are protected from any threat of damage.

"Working on that was protecting my bedtime stories," said Johnson. "Just, as an African-American kid growing up in Los Angeles, I'd hear a lot of stories from my parents, my grandparents, my great-grandparents, some of those stories manifested visually in the gallery of the Center for Civil and Human Rights. I took that personally, 'I need to protect this.'"